Technical debt is often described as something that “happens”. A side effect of moving fast. A mess left behind by a previous supplier. An unfortunate phase the business will tidy up later.

That language is comforting. It is also inaccurate.

Debt is what happens when trade-offs are hidden. It is the cost of decisions that were made implicitly, without being recorded, priced, or owned. Mature work does not pretend debt will not exist. It names it, explains it, and accepts its cost explicitly.

The real problem is not debt. The problem is unpriced debt that silently accumulates interest.

Debt is a decision, even when nobody admits it

You take on debt when you choose speed over stability. Or flexibility over constraints. Or launch over operational readiness.

Those can be rational choices. The failure happens when the choice is framed as “just for now” with no plan for the “later” part.

Examples in a website context are familiar:

- choosing a page builder because it gets to launch faster

- adding plugins to avoid defining a content model

- shipping without a change process because “it is only a small site”

- skipping documentation because “we will remember”

- running updates ad hoc because “it has been fine so far”

Each choice creates an obligation. The obligation may be small at first. It compounds as content grows, as more people touch the system, and as dependencies change outside your control.

Debt is not accidental. It is the unpaid portion of a trade-off.

Hidden trade-offs create interest

The “interest” on technical debt is not a financial metaphor. It shows up as operational friction.

You feel it as:

- changes that take longer than they should

- behaviour that is hard to predict

- upgrades that are stressful

- bugs that return because root causes are not addressed

- reliance on a single person’s memory

- repeated “one-off fixes” that become permanent

Interest is the cost of uncertainty.

When decisions are not recorded, teams cannot reason about consequences. They guess. They avoid. They postpone. That avoidance increases risk. Increased risk makes postponement feel sensible. The system drifts.

This is why debt can exist in “clean” codebases too. If the operating decisions are unclear, the system becomes fragile regardless of syntax quality.

Naming debt is part of professional work

The most practical difference between immature and mature delivery is not tooling. It is how trade-offs are handled.

Mature work does a few things consistently:

- it states constraints

- it records decisions

- it makes trade-offs explicit

- it defines what “done” means operationally

- it prices future work honestly

A decision record can be short. A few lines are enough:

- What was chosen?

- Why was it chosen?

- What was rejected?

- What debt does this create?

- What would trigger a revisit?

This makes debt governable. It allows a future team to understand intent, not just outcome.

It also changes the tone of planning. You stop pretending the system will be perfect and start managing it like infrastructure.

When debt is rational, and when it is negligence

Not all debt is bad. Some debt is sensible.

If you are validating a new offering and you need to learn quickly, you may accept debt as a temporary cost. The key word is temporary. Temporary requires a time limit, an owner, and a repayment plan.

Debt becomes negligence when it is used to avoid responsibility:

- “We will tidy later” with no budget

- “It is only a small change” repeated weekly

- “We cannot touch that” because nobody knows how it works

- “Updates are risky” because dependencies are unmanaged

Those are not technical issues. They are governance failures.

A stable system can carry debt. An unmanaged system turns debt into a permanent operating condition.

Trade-offs you should state upfront

If you want to avoid accidental debt, state a few trade-offs explicitly at the start of work.

- Speed versus stability: what is the acceptable level of risk at launch?

- Flexibility versus coherence: how much freedom do editors actually need?

- Dependencies versus ownership: what are we willing to rely on externally?

- Custom code versus maintainability: who will own it in two years?

- Short-term cost versus lifecycle cost: what is the maintenance budget?

These questions are not abstract. They set constraints that protect the system.

They also protect the relationship. Many project disputes are debt disputes. One party assumed the debt was acceptable. The other assumed it would not exist.

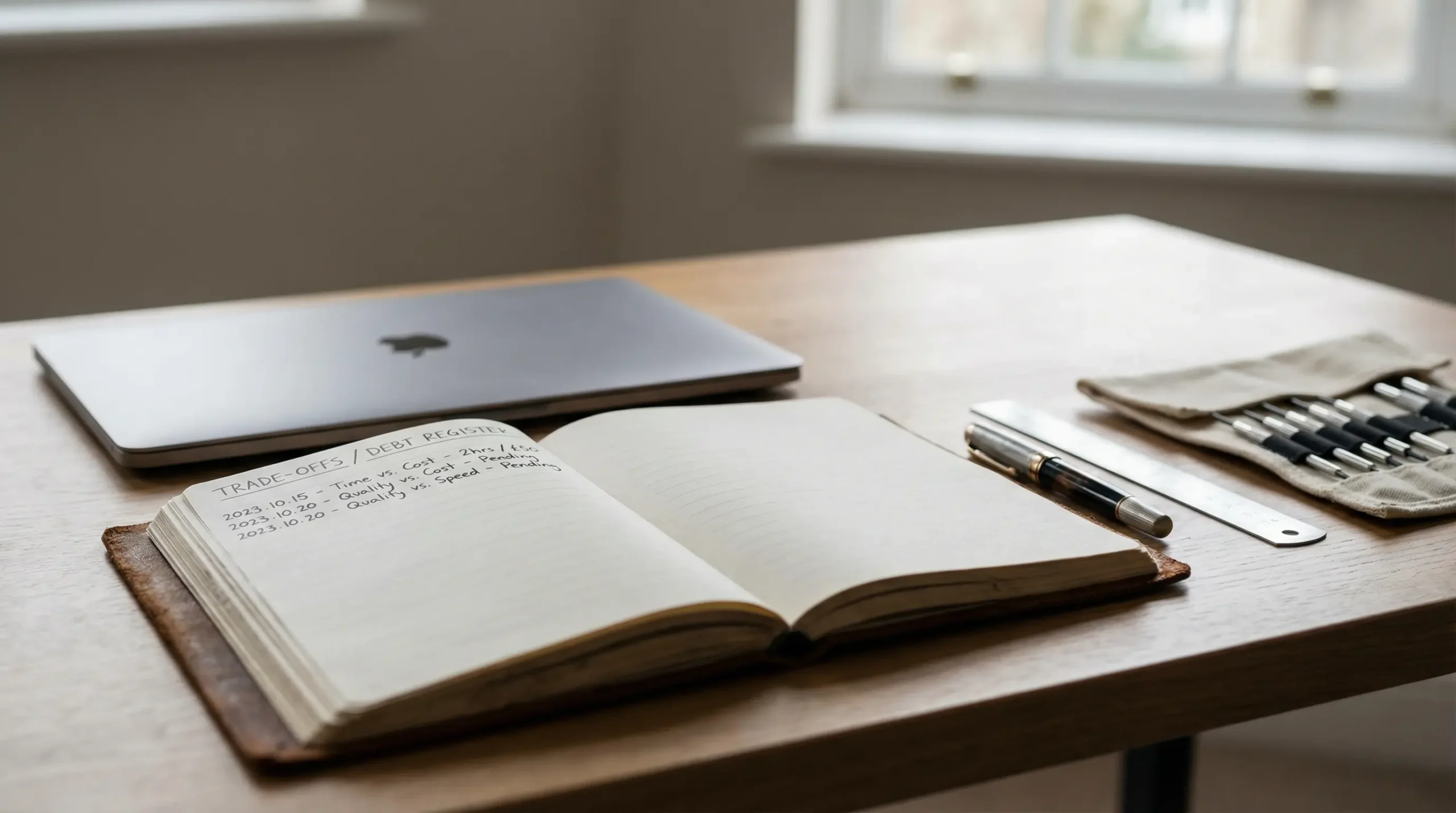

A way to keep debt visible without bureaucracy

You do not need heavy process. You need a simple routine.

Maintain a debt register. Keep it short. Review it monthly or quarterly. Each entry should have:

- description of the debt in plain language

- consequence if ignored

- estimated cost to repay

- owner of the decision

- trigger for repayment (date, event, risk threshold)

This turns “we should tidy up” into an actual decision. It also forces prioritisation. Some debt is cheaper to carry than to repay. Some debt is existential because it blocks upgrades or creates security exposure.

The point is not to eliminate debt. The point is to stop lying about it.

If it looks like a fit, we start by surfacing the hidden trade-offs: dependency surface, content model compromises, and operational gaps. Then we decide what debt is acceptable, what must be repaid, and what constraints will prevent new accidental debt from forming.

Related context: → Technical Refactoring and Consolidation